Inspired by the Council’s Rachel Tanur Memorial Prize for Visual Sociology, we ask prominent scholars to select a visual artifact of this time that will help future researchers understand the Covid-19 crisis. In this installment, Jill Fisher (professor of social medicine at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) spoke with Clare McGranahan (associate director of communications) about the pandemic’s effects on volunteer clinical trials, and its implications for the research enterprise more broadly.

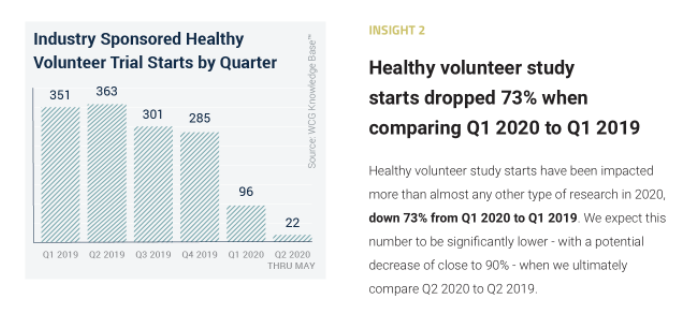

Photo Credit: WCG Clinical Knowledge BaseClare McGranahan (CM): You selected a chart that shows a sharp decline in healthy volunteer trials during the Covid-19 pandemic. Why did you select this for the time capsule?

Jill Fisher (JF): I chose this chart because the pandemic drew so much attention to clinical trials, but most of the focus was on the rapid increase in clinical trials and the amount of vaccine research that was taking place, as well as for Covid-19 treatments. In a way, that focus on Covid-19 research can make it easy to forget that a substantial portion of the rest of the research infrastructure shut down during the pandemic, especially for the first six months, but maybe even the first year of the pandemic. I feel like things are just finally getting off the ground again here at UNC.

To me, it was striking that there was more attention than ever to clinical trials, but not much attention to the fact that so much of everyday clinical research had basically shut down during the initial stages of the pandemic, particularly when it comes to healthy volunteer trials. These are the clinical trials that are done to test the safety and tolerability of new drugs or to get generic drugs on the market. And so I thought the chart’s depiction of the huge drop-off in the number of clinical trials that were done on this population was particularly striking.

And as context for why phase one trials and healthy volunteer trials in particular might have had such sharp declines, it’s because so much of these clinical trials are run as confinement studies. The participants actually have to check in to a research facility and stay there. And so you can imagine that during the pandemic, this would be particularly difficult. If someone comes in and they were positive for Covid-19, everybody would get infected.

There was really no industry guidance on how to continue to run these confinement-based clinical trials—there was no way to do them remotely or anything, and so it really did essentially shut down the healthy volunteer clinical trials that were not Covid-related, and I think the graph really shows the extent to which that happened.

CM: What are the longer-term implications of this decline in healthy volunteer trials?

JF: I think there are some implications for research and science, but also implications for the people who normally participate in these clinical trials.

In terms of the research and science, what it meant was that you could have all of these promising new drugs in the pipeline whose whole clinical development program got paused because they couldn’t run trials on healthy volunteers. They had to wait until they got the green light that it was safe to do them again. The FDA finally did release guidance in January 2021, giving industry some indication of how they can run these trials safely. That means that drugs for cancer, for diabetes, for all of these non-Covid-19–related things got delayed by at least a year because of the pandemic. That aspect of Covid-19’s impact on research is kind of invisible.

The other part of it is that much of my work has focused on people who serially enroll in phase one trials as healthy volunteers because they are paid for their participation. When I saw this graph for the first time, what I thought about was the fact that in a country with so much social inequality like the US, a lot of people rely on phase one trials in order to earn an income and make ends meet. So when I saw the graph, I thought about all these people that I had met over the years who did clinical trials either regularly or when they needed a source of income, and that even though it’s a problematic safety net, that safety net was taken away from them. During the pandemic, when people needed income more than ever, this was eliminated as an option for them. So I think that’s another important part of thinking about how income inequality accrued in all these other invisible ways during the pandemic.

CM: There’s been a lot of attention surrounding clinical trials during the pandemic. Is there anything you wish people understood about these trials that’s not being talked about?

JF: In some ways it’s really a mixed bag in terms of the attention to clinical trials. I think people are much more aware that clinical trials are needed to get drugs or vaccines on the market, and it’s great to have that kind of awareness of what it takes to get a new product approved. But I think that because of Operation Warp Speed, and because so many of these vaccines have been successful in the sense of being able to get on the market—at least with emergency use authorization from the FDA, it does create an overly positive image of drug development and its success. That perception probably need some correction, so that people really understand that the majority of products that are being tested will never make it to the market—that they’re not going to show that they are effective enough or safe enough to get FDA approval.

The other aspect of it is that there’s been so much rhetoric about FDA approval, or even emergency use authorization, as proving that a vaccine or therapy is safe. I think that’s a really problematic narrative too, because the FDA isn’t really saying it’s safe. What they’re saying is that it’s safe enough to warrant approval or an emergency use authorization. I’m worried that people are going to believe that the FDA is really saying, essentially, that there are no risks to taking medications or vaccines that are approved, when in fact that’s not the case. What they’re really saying is that the benefits of those therapies justify whatever risks they have, and that’s a really different kind of thing than saying that something is safe. Despite people’s greater awareness of clinical trials now, I think the pandemic has fostered a false sense that the FDA vaccine and drug evaluation process is actually saying something that it can actually never say.

CM: Looking back 10, 20, or 50 years from now, what do you hope that social researchers, and medical researchers, will take from this image?

JF: Again, it’s really important to emphasize how the pandemic negatively affected the research enterprise more broadly. A lot of what we’re focusing on now is the success story of the vaccine development—which is really important; I don’t mean to take away from that—but it’s really not just a story about the amazing volume of research that was done in 2020; it’s also about the amount of research that was stopped in 2020, and I think that part of the story needs to be told.

What does that mean in terms of how clinical trials will develop in the future? The pandemic has shown that we could do a lot of things remotely. Should clinical trials be changed, not just so that they’re pandemic-proof, but because the pandemic has shown that there are ways to make clinical trials more efficient, more generally? The pandemic created a situation where we’re questioning how the research enterprise runs. Future researchers need to think about more than just the Covid-19 trials. They need to consider how the pandemic affected all these other aspects of clinical research.

I think it remains to be seen what kinds of effects the pandemic will have on standards of efficacy and safety for future therapies that are approved or receive emergency authorization. The unprecedented number of emergency use authorizations that have happened during the pandemic is really important to consider in terms of what it means for the future. Will companies use that route more often for other therapies in other areas of treatment not related to Covid-19? It will be interesting to see how a lot of these things play out over the next couple decades.

This conversation was conducted on May 28, 2021. It has been edited for length and clarity.