Inspired by the Council’s Rachel Tanur Memorial Prize for Visual Sociology, we ask prominent scholars to select a visual artifact of this time that will help future researchers understand the Covid-19 crisis. In this installment, David Lazer (University Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Computer and Information Sciences, Northeastern University) spoke with Jonathan Hack (program officer, SSRC Anxieties of Democracy program) about how Covid-19 has shown the usefulness of computational social science and digital tracing to produce constructive and actionable policy initiatives.

Jonathan Hack (JH): Could you explain what commentary this graphic offers on Covid-19?

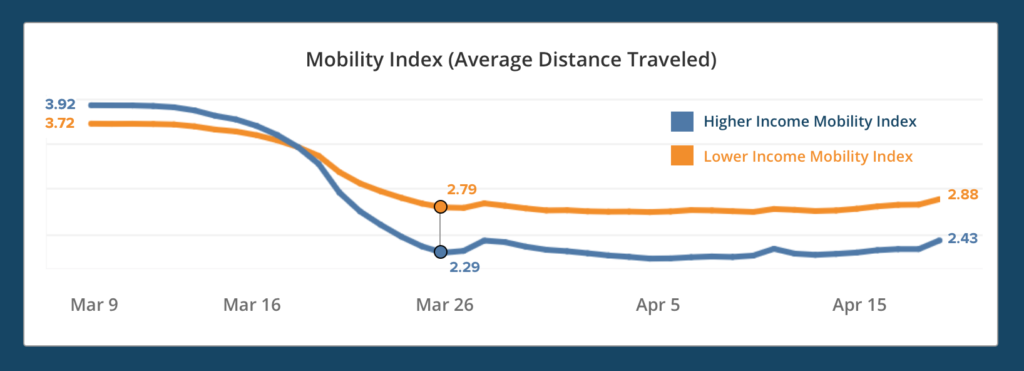

David Lazer (DL): It captures multiple concepts. One element is the literal interpretation, which is about inequalities. Covid-19 has revealed that some people were able to insulate themselves from the virus, whereas others were not or were less able to, and these data display this quite starkly. As one might guess, generally, those who have lower incomes and are less educated are more likely to lose their jobs. And, if they were able to keep their jobs, they are less likely to work from home, as reflected in the delayed reduction in mobility for people in less affluent neighborhoods.

A second story here is the nature of these data and that these kinds of digital trace data allow important insights at a remarkable scale and granularity. With such tracing, we get daily behaviors, allowing one to drill down and look at data within neighborhoods, within cities—something that would have been impossible in the past.

The third thing to take away is that we’re all being tracked. The journalistic outlets along with other media and scholarship have shown the realities of surveillance, which is not novel, per se. But the granularity of these data underscores the double-edged sword that comes with greater analytical capabilities.

Fourth, such data capabilities raise questions about collaborations around tracking mobility. How do we structure the not just academic, but in this case, journalistic enterprises around proprietary, sensitive data?

Finally, this graphic, a version of which was run in the New York Times, in some sense reflects the maturity of computational social science. When these sorts of things are represented in leading news outlets, it is a testament to the kinds of insights that can be drawn from these data and research questions. Hopefully, they are constructive and reveal actionable implications.

JH: There are always concerns around privacy and data. Do you think that the policy implications emerging from such granular research could convince people that the benefits of public health surveillance and contact tracing in certain ways outweigh privacy concerns?

DL: My hope is that it persuades people that there’s knowledge to be produced for the public good. These kinds of data are being used to help build better models for understanding and predicting the spread of the disease, allowing us to react more effectively.

That said, these kinds of data are not necessarily being collected for the public good. There are complex conversations to be had by society about how digital trace data can be used. Much of this work is done in “the black box.” Data enters the machine and through some computational processes arrives at an outcome. This is to say that we need to better understand the computational decision-making process and figure out what kinds of data are needed to arrive at good determinations.

For example, life insurance companies can take into consideration gender, along with a host of other factors, when determining premiums. This has implications for access and affordability. Another example would be digital tracing companies’ ability to see that you’re going to the oncologist more frequently. What does a company do with this information in terms of financial decision-making? What inferences can we make about who you are and your personal circumstances? In the end, the machine is making decisions about your life. There will perpetually be the question of how to integrate these concerns into a public discourse about what is acceptable and what isn’t acceptable.

JH: What role do you see social science and scientists playing in the discourse about the role of data in informing the public good?

DL: A significant amount of social scientists’ effort should be focused on areas where they can help. What we decide to study should be, in part, driven by where we think we can do the most good. At the same time, there does need to be some deep theory building, otherwise we end up in an intellectual wasteland.

There is a dividing line between why we study something and what we find. For example, if a researcher supports the mission behind Black Lives Matter, but is studying whether protests fuel the spread of Covid-19, the researcher shouldn’t say, “I’m going to make sure that I find that the protests are not contributing to the spread.” This would be terrible science and would feed misinformation to decision makers.

Ultimately, if we can answer important questions that speak to democracy, collective action, public health and well-being, and the dynamic of society, then we are doing worthwhile research.

This conversation was conducted on June 25, 2020. It has been edited for length and clarity.