Inspired by the Council’s Rachel Tanur Memorial Prize for Visual Sociology, we ask prominent scholars to select a visual artifact of this time that will help future researchers understand the pandemic crisis. In this installment, SSRC president Alondra Nelson speaks with Brendan O’Flaherty (professor of economics, Columbia University) about the repercussions of the astronomically high United States unemployment rate resulting from the economic impacts of Covid-19.

Alondra Nelson (AN): Could you provide some context for the artifact you have selected and what you hope future researchers will gain from it?

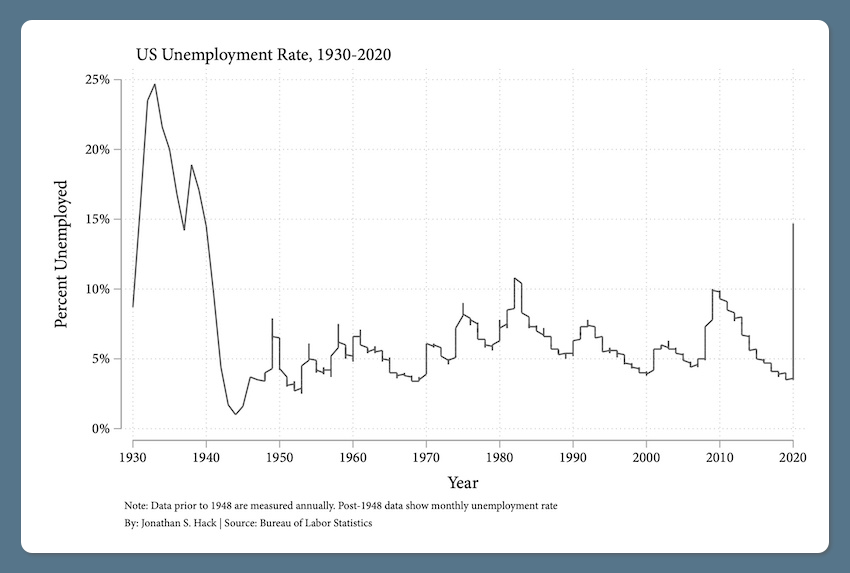

Dan O’Flaherty (DO): This is the long-term time series of unemployment rates in the United States. It starts with a very high unemployment rate of 25 percent in the Great Depression. Then it comes down and bounces around, and then you see the terrible recession of 1981–82, when the unemployment rate gets to be about 10 percent (as opposed to 25 percent in the Depression). And then we have 2020, currently at a 15 percent unemployment rate.

AN: We mostly lack historical precedents for this time, but what can we hypothesize about a rapid spike in unemployment levels and what the effects might be?

DO: We can’t hypothesize about what it means when unemployment rates rise this rapidly because it’s never happened before. The worst was during the Great Recession, when approximately 600,000 unemployment claims were filed weekly. For the week ending May 16, 2020, it was 2.5 million, four times the previous record.

We do know there is a relationship between unemployment and homelessness. And as you would expect, it’s a positive relationship. What happens if we get to 15 percent unemployment? What happens with homelessness based on this historical relationship?

I developed a projection that shows homelessness numbers rising from about 550,000, before the pandemic, to about 810,000. That’s a 40–45 percent increase. I believe that that’s where we, as a society, should start. Historically, Americans adjust to a bad economy by increasing household size. That is what happens in every recession—family members tend to move in with each other. What scares me is that there are real differences in the ability (and safety) of undertaking these adjustments between cities and rural areas. Looking at the historical data on big and small cities, what you would expect to see with 15 percent unemployment is an explosion in household size. Unfortunately, with this situation, with this pandemic, we do not have this option; we are unlikely to see an increase in household size as in years past.

AN: Why not?

DO: People are reluctant to share housing today. You don’t share housing and you’re very careful about with whom you will share housing. For example, most people are not going to share an apartment with people they’ve never met. And I don’t believe universities will continue to have dorm rooms with two, three, or four students in them.

AN: On the one hand, your projection is about the social-distancing mandate that we’ll be living under for a while to come. So, even if people want to live together with more density, doing so may be inadvisable from a public health perspective. And, on the other hand, you point to cultural and social norms that suggest that some are unlikely to want to live in a multigenerational household or to take in boarders.

DO: Yes. There are culture and social changes happening. What we are going to see in the long run is that people are not going to want to live with many roommates. They are not going to want to live with so many unrelated people in a household, which means there’s going to be more demand for living space. More demand for living space means higher rent.

The rising homelessness of the past five or six years has been concentrated in “superstar cities.” After Covid-19, whether or not Los Angeles, New York, Boston, and San Francisco will continue to be superstar cities is an open question. Whether or not you will have the same demand for office space, and whether or not people are going to move to New York in order to go in the theatre remains to be seen. This may reduce the housing pressure on big cities. But this demand for larger household size is going to be affecting every place in the country.

AN: The variables that we most often consider with regard to homelessness are housing capacity and housing density. Are there other variables that are driving this?

DO: The main driver in almost all economic predictions on homelessness is rent; rising homelessness could be offset by decreases in rent, especially in places like New York. But we don’t really have observations of rent at the current moment because many people are not paying rent right now due to the Covid-19-related freezes and evictions. We don’t know how the rental market will sort out.

AN: Thinking about a social researcher 50 years from now, what does the time series you selected tell them about the social impact of Covid-19?

DO: That this moment is when what we thought we knew about unemployment disappeared. We’ve never seen a change this sharp. The closest thing we have seen is the effect of the 1981–82 recession on the African American unemployment rate, which hit 20 percent. That was the only other time we saw a 20 percent unemployment rate, and that was the start of a really miserable decade. Today it’s near 20 percent.

One of the other things to think about is whether a rise in homelessness will be shown to perpetuate Covid-19. We’re supposed to stay home and wash our hands all the time. And if you’re homeless, you can’t do either. If the historical relationship between unemployment and homelessness holds, then you’ll have a group of people who will probably be more vulnerable to Covid-19 and, therefore, to increasing the spread of coronavirus in the second and third surges.

This conversation was conducted on May 21, 2020. It has been edited for length and clarity.