Inspired by the Council’s Rachel Tanur Memorial Prize for Visual Sociology, we ask prominent scholars to select a visual artifact of this time that will help future researchers understand the Covid-19 crisis. In this installment, Adia Benton (associate professor of anthropology, Northwestern University) spoke with Jonathan Hack (program officer, SSRC Anxieties of Democracy program) about how Covid-19 has uncovered America’s uncomfortable relationship with knowledge and expertise.

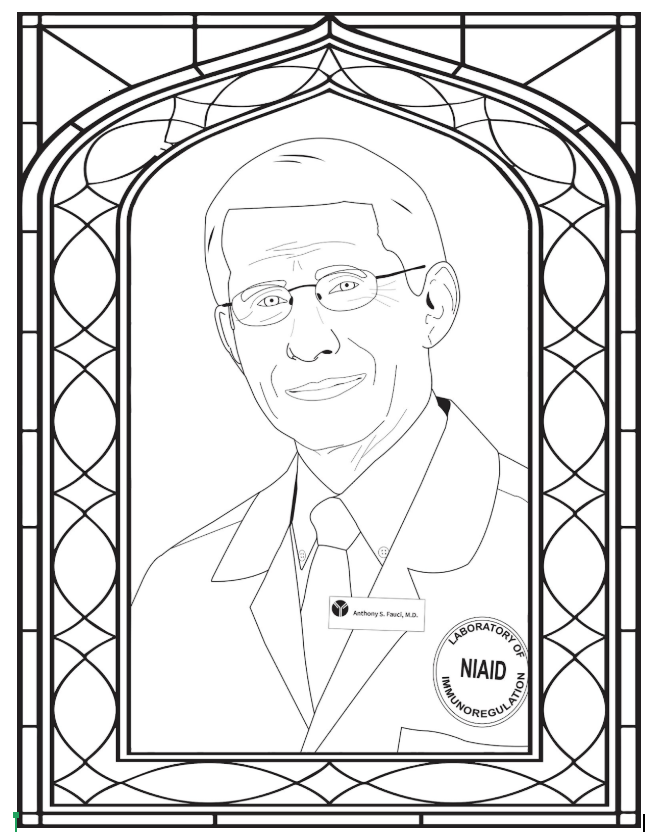

Jonathan Hack (JH): What motivated you to select this image of Dr. Anthony Fauci as a saint?

Adia Benton (AB): During the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Trump administration held daily press briefings, where they tried to confine the spectacle to Trump himself. During those daily briefings, there would be six or seven people on stage—Trump, Pence, sometimes the surgeon general, sometimes Dr. Deborah Birx. They offered a lot of information. Some of the information was suspect, rambling, or obfuscatory, or all three. Meanwhile, Fauci was stealing Trump’s thunder. His matter-of-fact way of speaking, his long-established expertise… all of this was in tension with the spectacle that Trump wanted to create. So much so that “straight-shooting” expertise was elevated to the level of saintliness.

By simply being an expert in viruses, in public health, and saying things that, frankly, sound reasonable (and reasoned), he stood in stark contrast to the rest of the spectacle of the daily press briefing. For me, Fauci’s growing popularity was an interesting commentary on our times, highlighting America’s relationship to knowledge. In his own performances of expertise, Dr. Fauci has to reckon with and acknowledge the deep-seated, defiant ignorance of this administration, while also finding a way to offer advice and counsel under these circumstances. His ability to navigate this and speak with a certain legitimacy and authority about Covid-19, a novel virus that we knew very little about, allowed him to emerge as a “saint.”

JH: With the rise of misinformation and active attempts to discredit expertise, what, then, is America’s relationship to knowledge?

AB: In many ways, the Trump presidency—while I’m not sure if it is representative of the country—does show a distrust and disenchantment with elites and “disingenuous politics.” Americans say things like, “Capitalism is good,” or “Government should be run like a business,” and, in doing so, chose someone who was overt in his ignorance and outward in his anti-intellectual stance. Interestingly, this is read as “plain speak,” which is something Americans seem to value—“straight talk; plain talk.” They also get this from Fauci. But it is buttressed by the legitimacy of scientific expertise, which seems in short supply in the public, official response to the epidemic.

One of the things I find really interesting about Trump is the “spectacle” that is Trump. By this I mean, he’s not afraid to constantly arrange a show for us, to control the kind of information and knowledge that circulates, to say things that are absolutely false. So long as he’s telling us something, filling up the space with something, there is so much information overload that we don’t have a chance to refute it. This is best seen with the daily press conferences. They are two to three hours of Trump talking, and if someone says a fact or offers a contrary point, he doubles down with even more falsehoods.

Knowledge, once a public good, has become a commodity. It is a question of who controls the information and whose knowledge or expertise is legitimate. What we are seeing with Trump, and his response toward messages that contradict his own, are more falsehoods, more outlandish claims in hopes that no matter what, it is his message that is carried at the end of the day.

JH: What do you see as the lasting effects of Covid-19 on American society?

AB: I am writing a book about Ebola. This process has been confirming a lot of things, but also forcing me to rethink whether the conceptual and theoretical frameworks I’m working with are useful for thinking through how societies react under a health emergency of this scope and scale. We are seeing an extreme official, government response with shutdowns, lockdowns, and quarantines, all necessitated by our failure to do some pretty basic things: funding public health and ensuring a just, equitable, affordable, and high-quality health-care system.

This epidemic has revealed what happens when the state fails to support the public good; public health and health care are only a part of this picture. Without the ability to care for the general population, without a social infrastructure to “weather the storm,” we are forced to rethink the nature of our economy, the extent to which employers should fund our health care, and what work ultimately becomes essential. There is a lot in our collective consciousness that is being awakened by this outbreak.

This conversation was conducted on July 7, 2020. It has been edited for length and clarity.