Inspired by the Council’s Rachel Tanur Memorial Prize for Visual Sociology, we ask prominent scholars to select a visual artifact of this time that will help future researchers understand the Covid-19 crisis. In this installment, Elizabeth Hinton (associate professor of history and African American studies, Yale University and Professor of Law, Yale Law School) spoke with Clare McGranahan (associate director of communications) about Covid-19’s impact in jails and prisons, and the connection between mass incarceration and the failures of the US pandemic response.

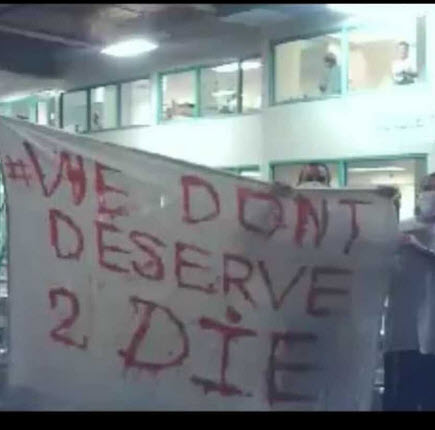

Clare McGranahan (CM): You selected a photo of inmates holding up a sign at a jail in San Diego county. Can you talk a little bit about why you selected it?

Elizabeth Hinton (EH): When Covid-19 first broke out, I was most immediately concerned for my friends and family members who are in prison, in part because people in prison can’t social distance, they don’t have access to ample soap and other kinds of cleaning supplies, not to mention PPE and masks and things like that. Prisons are already a breeding ground for infectious disease.

So while we were all quarantined and everybody was doing crazy things like spraying down groceries, trying not to get infected, I was thinking, what’s going on inside prisons? And it’s so difficult to actually get accurate information. I started receiving messages from a family member who was incarcerated at the California State Prison at Corcoran via JPay, which is the email service that many people in prison use, and he was telling me about how the virus was spreading in his cell block, how people were being quarantined, and how terrified he was. He felt like it was only—it is only—a matter of time before he contracts the virus himself, although he hasn’t, thank God, contracted it yet. And I know at some federal prisons people who test positive for the virus are being quarantined in tents. So the conditions are horrible and the treatment is horrible, and this is true of the American prison system as a whole, but it’s only been exacerbated and kind of come to the surface with Covid-19.

The message from the George F. Bailey Detention Center in San Diego really makes it plain: people in prison don’t deserve to die. And in response to the fact that the people confined at the jail hung this sign and contacted the San Diego Union-Tribune to try to bring awareness to what was going on, the Sheriff’s Department placed these incarcerated activists in isolation as punishment. So they were essentially punished for trying to inform the public about what’s going on inside.

I thought this was an important photo to show in an attempt to continue to spread awareness about the problem of Covid-19 in prisons, which is something that hasn’t really come to the center of our discussions about the pandemic.

CM: How do we keep this issue on the forefront of people’s minds, even after the pandemic is over?

EH: I think that those of us who have done this advocacy—and a lot of people have done really good work on the impact of Covid-19 in prisons—have helped to bring attention to some of the larger problems in the American criminal legal system and our system of punishment that has systematically incarcerated majority low-income people of color, many people lacking even a high school education, and put them in prison under draconian sentences for very, very long periods of time.

The Covid-19 crisis has given us an opportunity to reexamine many of the fundamental problems in our society, mass incarceration being one of the foremost problems. We need to reevaluate how we lock people up and why we lock people up for as long as we do. Because many of the people who are in prison should not be, and many of the people in prison were locked up during the height of the war on drugs in the ‘80s and ‘90s, because of mandatory minimum sentences, three strikes laws, and crimes related to marijuana and drugs that have since been decriminalized. They were arrested and convicted at young ages and are now much older men who no longer pose the “threat” to society that they did decades ago. They are also, because of their age, more vulnerable to developing severe complications from Covid-19.

We need to reckon with the history of over-policing and reckon with the origins of harsh sentencing practices, and then not only release people, but also then think about how we might be able to decarcerate on a larger scale and change our sentencing structures in the future.

CM: Beyond getting people out of prison, do you think that there is momentum to enact the kinds of social policies needed to support people once they’re released?

EH: I hope so. I think it’s part of a larger conversation that emerged during the protests for racial justice in the summer of 2020 that really began in response to the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. These racial justice protests constituted the largest social movement in US history, and I think it is deeply, deeply tied to the Covid-19 pandemic. The two cannot be separated. And that movement has called us to think about how we might realize a different set of investments in low-income communities and communities of color in particular, outside of policing and surveillance and incarceration.

This has been captured in the slogan “Defund the police,” which I read as a call for a divestment from prisons and police forces and an investment into those social supports—education opportunities, job creation, guaranteed income, decent housing—basic things that, frankly, federal, state, and local governments have failed to provide for our most vulnerable citizens. And again, all of this is exacerbated by the virus.

CM: As a historian of inequality, are there lessons you think that we can take past instances that similarly felt like a turning point, when there was potential for change?

EH: In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War in 1865 and the height of the civil rights movement in 1965, like today, the United States was at this crossroads, where many of the inequalities, or the ills, or the viruses of society were exposed and were being confronted by officials at the highest level of government in new ways. These viruses include things we’ve been talking about: undereducation, joblessness, underemployment, and, of course, systemic racism and inequality.

So, in that sense, we’ve been confronted with these questions before, and I think the task now is: How are we going to respond so that we’re not confronted with these questions again? Now that these viruses have been unmasked, and the impact of Covid-19—especially in low-income communities of color and prisons—has been exposed, what are we going to do to ensure that in the future, we can create a more equitable society with greater social supports, so that the next time we’re faced with a global pandemic, we’re able to respond much more effectively?

CM: What do you hope future social researchers looking back on this moment in history will take from this image?

EH: I think this message, “We don’t deserve to die,” really helps us reflect on and explain why the United States has done a particularly poor job in combating Covid-19.

There’s a direct correlation and a history behind the fact that the United States is home to the largest prison system in the world and the place with the highest number of coronavirus infections and deaths in the world. Instead of spending money on things like health care and a guaranteed income and full employment, we allocate taxpayer dollars to police and prisons, and this has left us underprepared to really confront the crisis of mass incarceration and the crisis of Covid-19. And we’re reaping the consequences now.

This interview was conducted on February 3, 2021. It has been edited for length and clarity.